WINNER OF THE COMEL AWARD 2012

Interview to Massimo Drisaldi

by Rosa Manauzzi

Massimiliano Drisaldi was born in Rome in 1939. He attended the free school of nude of the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome and engraving courses at the Art Center “Architrave”, where he studied all metal engraving techniques. It is one of the most important representatives of the Roman engraving school. He is a rigorous Maestro of the different techniques of engraving and lover of the Roman-pontine landscape.

From 1974 he devoted himself to the artistic activity as an engraver and painter. He has participated in numerous Art collective exhibitions, national and international, as well as solo exhibitions, even if less numerous.

In recent years his artistic activity turned mainly to engraving, creating over three hundred and fifty slabs.

In the 80s he was a teacher as part of a series of seminars organized at the Centro Polivalente of cultural activities, at the Rivaldi Palace in Rome, giving theoretical and practical courses, along with major artists working in the field of engraving (including Attardi, Calabria, Fodaro, Maccari, Velly, Vespignani). In 1990 he was one of the selected engravers to represent Italy at the “Intergrafik 90”, the ninth International Graphic Triennial, held in the former German Democratic Republic.

In 2012 he won the “COMEL Award Vanna Migliorin – Contemporary Art” with the work “Winter”, (drypoint on aluminum 500 x 700 mm). In 2013 he was awarded the Image Prize for Art.

Introduction by the curator

Massimiliano Drisaldi was the first winner of COMEL Award in 2012. Since then other four editions have followed. I met the brothers Maria Gabriella and Adriano Mazzola just before the second edition. They involved me in the concept and I immediately embraced the idea of enhancing the prize by making it international. I would have therefore been in charge for the communication and translate ideas and projects that were gradually presented.

Only recently we decided to collect the testimonies of the artists intervened in the various editions to make a catalog. For this reason, it was necessary sometimes to go back, finding the participants selected for the prize a few years later. A meeting that is always a big exchange of a lot of emotions, in the name of art.

Massimiliano Drisaldi has happily welcomed us into his studio, generously revealing tools, techniques and a huge amount of works. Faces of children, animals, withered faces of old people met by chance in the villages; realizations with etching, aquatint, soft wax, drypoint.

The study is full of precious folders of which the Maestro remembers perfectly the placement and the genesis. On the walls there are art gifts and among them some portraits of the Pontine Agro and the Roman Agro stand out. They represent the daily challenge searching for the perfect hue, a black that can be developed differently in a thousand shades, depending on how the hand can itch, firmly and poetically.

In an adjoining room there are spacious and bright paintings in which colors seem to breathe. Drisaldi spares no effort in creating art and showing it, explaining content and techniques. As the great Masters, aware of their own path, he regrets that today there are very few young people who want to venture out in the engraving.

“I think of the Sistine Chapel,” he says, “and I wonder what monster talent can have finished it, but then I just tell to myself he was an artist who took the time to create art”. A sentence that well gives an idea of his ongoing commitment over time, a life for art, a gallery of places and humanity that seem the result of more artists and more lives. Instead it is the work of a single person who has worked with great dedication and tireless passion.

With the work “Winter” you have been the first winner of the COMEL Award, just a year before it became an international prize. A happy coincidence, as both the creation of the prize and your artistic activities are heavily indebted to the Pontine territory, which both contribute much to make known. What did you think of this particular landscape, given that historically it has always been able to arouse fascination and to invite at least to a stop in order to better know and to represent it?

Creating this work with the technique of drypoint has been a challenge. I had never created a work 50x70cm. It needed a whole month to finish it. I consider it a real sculpture.

I feel very close to the Pontine territory and the Agro Romano, they have much in common. I know them well, I have lived there, I can easily give testimony of them because they are part of me. They deserve to be observed more, they deserve all the possible attention. I do it in my own way, I portray them, carve them.

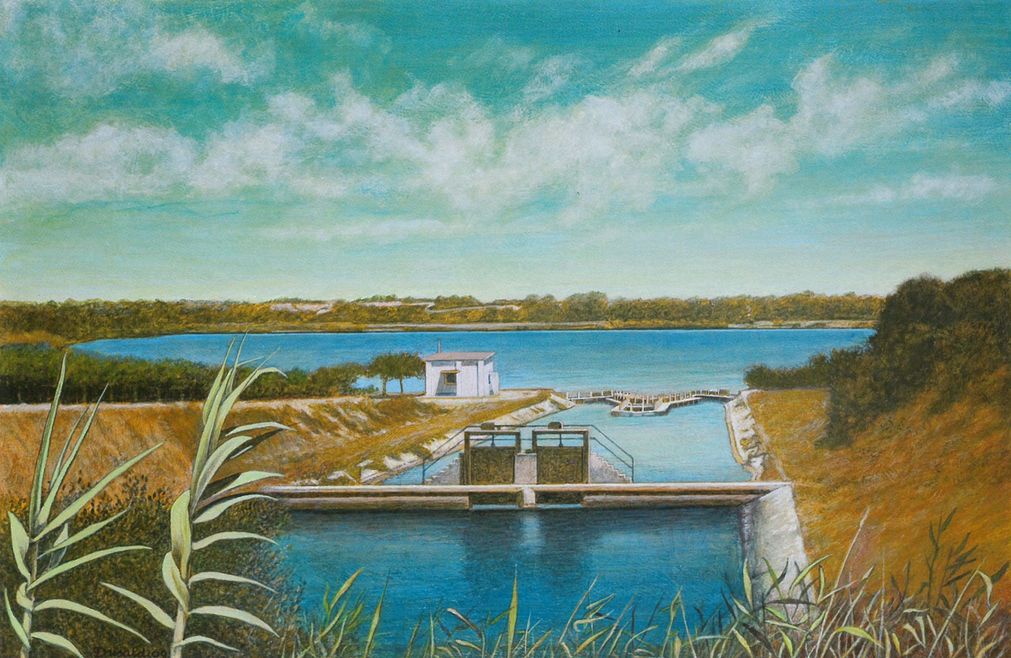

The canals of the Agro Pontino have made the history of Latina – the local writer Antonio Pennacchi wrote a book titled Canale Mussolini, which won the most important Italian literature prize, the Premio Strega, in 2010. Yet today they seem to have fallen into oblivion. The inhabitants notice of their presence only in the case of threatening floods. Even the administrations that have occurred over time have not done anything to valorize the routes. On the contrary, your art has transformed them into real memory monuments. You manage to draw a personal emotional geography ready to become collective for any exhibition occasion.

It’s our history. My story. I do not think they can do without. We need a memory to better live the present. I hope to enhance these places with what I create.

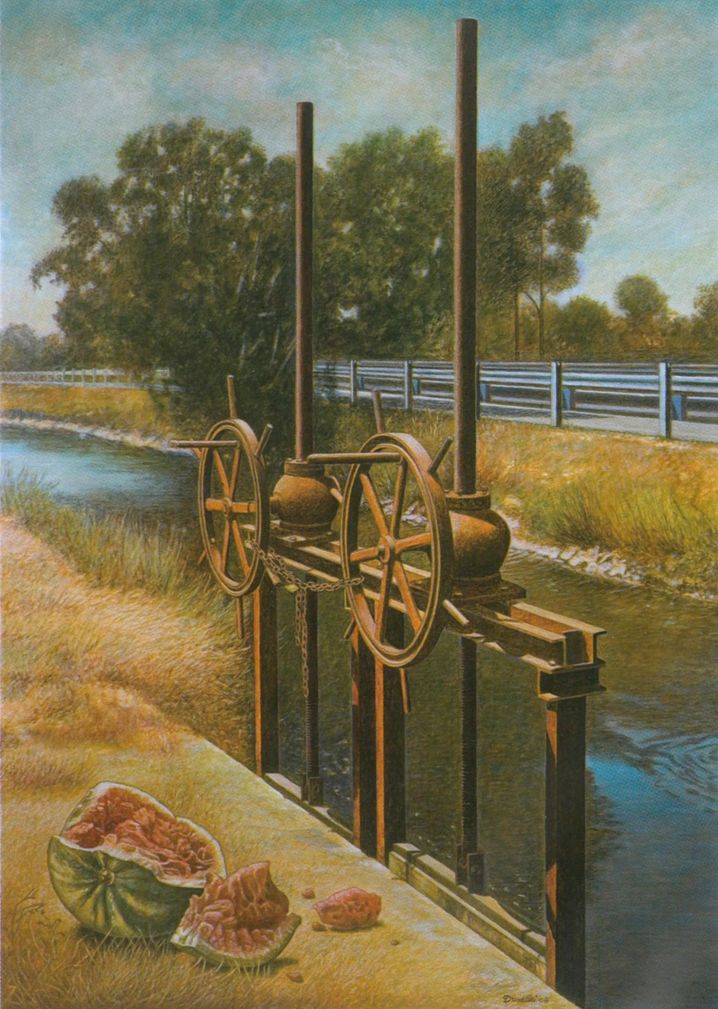

Canale di bonifica – 2009

You’re a master in engraving techniques: drypoint, burin engraving, etching, aquatint, soft wax… maybe these techniques are not so profitably used on the market and require a long and rigorous application. They also represent a testimony of the alchemical work of the artist, which transforms the raw materials in silence and stay away from the clamor. You chose the expertise and so much technical perfection that you required a customized printing press. The creation that you get is always original and intimate, it seems to reflect a certain reluctance to the crowd, a little chromatic melancholy; but it can also create a celebrative and outwardly imposing creatures – as in the case of ‘Saint Michael’.

In all this, what is your relationship with loneliness and with the public?

I was not born as an engraver. I started out as a painter. It is actually a kind of genetic code that you carry inside, but you have to become aware of it over time, you have to find it out. There has to be an opportunity that creates the engraving artist. You work on a zinc plate, or a copper one, a mirror polished plate. At the beginning the plate caused me fear. It requires a thorough job. A little distraction may ruin it forever. You see, all the equipment is made by me, including the printing press. I created it so that no effort is necessary. It could also be used by a baby. And I can print without having to rely on a printing studio.

On the plate you roll out a thin layer of wax-based paint, which serves to protect it from the action of the acid, then with a pointed etching needle you draw on the plate. In this way the acid corrodes only where the pointed etching needle scratched the paint.

The turpentine then removes the protective wax. It’s a lonely and alchemical job, a challenge even with yourself. The engraver uses nitric acid, facing serious health risks. The exhalations are dangerous. However, the result is incredible. I started with the etching and aquatint techniques, deepening later all the other metal engraving techniques. In the end I blended them all on the same plate.

The audience arrived unexpectedly, I have not searched for it. I started timidly. Maybe now I regret a bit the fact that I haven’t shown off a bit more. They all do it, even those who do not produce much. But shyness is part of my character, I’m happy anyway for how things have gone.

I started to engrave just for fun, thanks to the advice and support of Carmelo Fodaro. The first engravings date back to 1975. We did two plates each, his wife Giulia printed them. And we sold them. Unbelievable. I realized that what I produced was appreciated by the public and through this little experience I began to realize that the engraving represented the main road for me. The first impact with the audience was when I worked at the State Monopoly. A painting contest was organized and I won.

What an incredible joy! I did not expect it at all!

Draining pumps, canals, sluice gates, acrylic paintings on canvas. They are geometric figures that are faithful to the architecture. Nearly cloaked color photographs. The ‘objects’ are themselves a representation of the artisan and industrial perfection (masterfully made from the artistic point of view) that has enabled man to draw a whole territory, just like a project on a canvas of vital humus. The monuments, which you wanted to make everlasting in their beauty, are now completely ignored. As an artist you offered the symbolic and functional value. The art seems the only way to give balance to the relationship between nature and urbanization.

I’m always very surprised when I see all these wonderful works hidden in the tall grass, not on display as they should. Sometimes I had to do small risky adventures to photograph the places. I went for shots on which to base my work with the help of my friend Massimiliano Vittori, one of the most competent collectors and connoisseurs of engraving. And together we tried to find the right play of light and shadow to be immortalized in the camera roll. It’s just an anecdote, that makes us understand that it is not always easy to find these places, but they exist and must be discovered.

I am very grateful to this land that gave me work and love.

Chiusa sul lago di Fogliano – 2008

You’ve portrait trees, lakes, old farms (the so-called ‘poderi’), the details of the vegetation with benighted connotations, using the etching and soft wax techniques. Each cane, each branch, holds the most obscure part of the history of the Pontine territory: light, marine hues, new life, as well as malaria deaths, mournful and sinister stagnation mournful. Yet the hope shines through, creating a gap between the dark clouds, thanks to full moons and bright peace after the storm (‘Torre Astura’, ‘Nymph’, ‘Podere One’, etc.). Salvation seems to come from heaven, scrambling, triggering, stirring the water that would otherwise be fatal and putrid stillness.

The Land Reclamation (bonifica) nobody talks about required an incredible contribution of lives. Thousands of willing people lost their lives. It is thanks to them that these lands are now livable and richer. You’ve got it right when you mentioned the darkness in my works, as well as when you mentioned that the light breaks through the darkness. There is always light after the dark, we have to know it. It has nothing to do with religion. I am neither an atheist nor a bigot. I recognize that this light comes from something else – I have no awareness of where it comes from exactly though. It may certainly also come within us. Now, as I become more involved in painting, this light seems to completely inundate my job. There is the sea, the sun is shining…

In the work ‘The Wave’ (etching, soft wax and burin on zinc), all the destructive force, and at the same time the vital force of water and sea, is felt. Such an immense power that no man dares to venture by any means, as it is seen instead as part of Hokusai’s work, which seems to have inspired your work or I perceive as being somehow similar to it. Nature does not grant any confrontation and could take back in just one second what Man has the illusion of having under control.

The wave is powerful. I would say that it may be monstrous in its power. It represents the full force of Nature and all the energy of the sea. It is the enormous strength Man uselessly tries to measure up against, or even worse, tries to dominate. Nature cannot be challenged, it is a lost cause. You can do nothing against water. The wave is a warning from the sea: you have to pay respect to the sea.You have to pay respect to Nature.

The tree (as in your works ‘Winter’, ‘The Oak’, ‘Poplars’, ‘Fleeing Trees’, etc.), roots and foliage, earth and sky, is a ubiquitous element and identify the Agro with specific species. Mythical being, rock god who may enchant for its size and distributes life. Resumed in the lushness of the foliage or engraved in the essentiality of the branches, it is the presence that distinguishes the character of an area. And that should be enough to save and revere it, not only with art. You know that the writer Antonio Pennacchi led a struggle in favor of the windbreak rows, that are becoming increasingly rare despite their preciousness. An unequal struggle with the continuing deforestation though. What do you think of trees?

The tree is life. It is beautiful and majestic. It has colors that change with the changing seasons. Everything about it is important: where it was born, where it is. It is the symbol of the territory which is also our home. When you plant a tree you say “I bed it out”, demonstrating that this will be the place which we will share with it. Unfortunately small excuses are sufficient for someone to destroy them for some imaginary trouble. We should remember that when there are no more trees we will stop living.

I love winter trees, leafless, which strike a strong mark, almost carved into the metal, which embraces the ink deep into its groove and then returns it, embossed, on the paper. I love to play variations of tones on my plate, continuing to bite them in the acid several times, in different times. It is not easy to get that color. And the works that I get are each one different from the other, just as each tree has a different color from the other.

Chiusa della foce di San Nicolò – 2009

The reviews to your exhibitions agree to define you one of the greatest engravers of Italy, a Master for inspiration. In your works one can see hints of William Turner, Caspar David Friedrich, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot… What were your reference points in your artistic career?

I really like Rembrandt, Piranesi and the Roman symbolist painters of the early twentieth century. I like Carlo Alberto Petrucci in particular. And I also like Sigmund Lipinsky. However, I have not followed them a lot, I have never followed any currents. I worked out a path of my own, favoring a discovery occurred within me. I started with the etching and aquatint, and then I used the drypoint technique.

Later I started to mix all the techniques. Now I’d like to obtain with painting what I have reached with the engraving. In the engraving I feel like I have given my best.