lifetime archievement award 2016

Interview to Valeria Gramiccia

by Rosa Manauzzi

Valeria Gramiccia works in a spacious and light-filled studio, in an attic in the Parioli neighborhood, in Rome. From her terrace, away from the traffic noise, you can see both the beauty of the capital, with its dome and its 360 degree skyline, and its ugliness, ‘the intruders’ as she calls them. Protuberances, built on top of the buildings, which weigh heavily on them.

The artist’s studio is rich in impressive artistic memories and testimonies. Here she was able to study closely with Afro and here she continued to live the art and guard the stratification of the many important experiences with other great Masters, along with the travels, the meetings, the events organized with other important artists.

When I enter the studio, in the company of the Spazio COMEL owner, Gabriella Mazzola, to start this interview, I already know that a special morning is waiting for us and the emotions start mingling and tuning in this direction. There is French music playing in the background. All around there are jars with colors, brushes, tables, and various work machines (for cutting, shaping, gluing, etc.). Some have been specially purchased for working aluminum, as the artist was inspired by the COMEL Award. While a pleasant aroma of coffee expands in the air, our first encounter with her works is through the bilichi, some of which are dedicated to the painter Novelli.

In seguito ci mostra i paracarri di Consagra (una rivisitazione contemporanea dei paracarri di Bernini), la sua “Città frontale”, risultato di un’idea utopistica di città occupata dagli artisti, che, secondo la visione del Maestro, dovrebbero in qualche modo ridare vita a città squadrate dagli architetti perché “La città non può essere concepita con riga e squadra”.

Inoltre ci mostra le sue misteriose scritture e preziose carte orientali su cui ama dipingere. Non si risparmia negli aneddoti e nel mostrarci l’arte di Afro, Consagra, e le sue opere. Seguire i suoi racconti è un’immersione affascinante nella storia dell’arte moderna e contemporanea.

Afterwards she shows us Consagra’s bollards (a contemporary revision of Bernini’s bollards) and his ‘Frontal City’, a result of a utopian city occupied by artists who, according to the Master’s vision, should somehow revive the excessively squared cities built by architects. He used to say: “The city cannot be designed with a ruler and a set square”.

Furthermore, she shows us her mysterious writings and precious oriental paper on which she loves painting. She does not spare herself in anecdotes and shows us Afro, Consagra’s, and her own works. Listening to her stories is like diving into the history of modern and contemporary art.

Valeria Gramiccia has always been a committed artist, and she claims that in the past art was more authentic, even politically. This characteristic has been lost. Galleries are gone, she says with regret. Years ago they were a place of encounter and confrontation, for artists and art lovers. ‘At six o’clock all artists were in the art gallery,’ she tells us about her experience at the Mara Coccia gallery [the prestigious Studio d’arte Arco d’Alibert, then Associazione Mara Coccia, opened in Rome in 1963].

She is nostalgic about an artistic creation free from the market, and she feels the lack of ideological clashes, which at least had schools of political thought behind. She thinks with concern about young people that today are more accustomed to passively accepting than to seeking. However, she recognizes an important value to education, which still represents hope: schools and families can still do a lot; they can give back the freedom and creativity. That is what she tries to do with her nephew, Bianca, whom she has carried around the world since she was six years old. Valeria herself was a child who has seen many countries, thanks to her father, one of the most important malaria scholars in the world, and thanks also to her free spirit.

“After 1948 he no longer used oil colors. He used powders, powder pigments, and Vinavil. Let’s say more precisely around the ’50s, because after the war, Italian artists, who came out from the war, fascism, etc., made their first trip to America. And in New York there was an art gallerist artist who turned out to be crucial to them, Catherine Viviano. She started to take care of them. Here Italian artists discovered the Vinavil glue, which in Italy did not exist. So this glue, with the pigments, also allowed Burri to do the cretti (cracks).

After all, the material influences the artist very much, it influences him a lot. Something like this happened with oil painting centuries ago in Italy. It arrived in Venice thanks to a painter, not of great fame, who went to town carrying with him the transparent oil. So the whole base of Tiziano’s paintings is tempera then polished with oil. Antonello da Messina was the first to use it as a medium. In my art the discovery of aluminum has brought a recent change, especially thanks to the COMEL Award. Even though I have not abandoned the paper, as I love it. Moreover, I always feel the urgency to use color.”

How did your artistic experience begin? And how was your choice considered in a context where women had to deal with other kind of stuff?

In my family we loved art and used to hang out with artists. The childhood spent abroad, with my parents, was crucial and enabled us to not be tied to the Roman conventions. I was lucky to have a very curious childhood because my father worked abroad. When I was six, I left for India, then I went to Egypt, Lebanon, then here and there. So this habit of moving, of travelling, has been important to make me feel at home wherever I have been.

Which schools did you attend and who have been your favorite artists over the years?

I attended the art school and then the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome. These were the years when the ‘great’ teachers taught, and among the high school teachers I had: Afro, Capogrossi, Novelli, Turcato. I’ve always loved Klee and Licini. I’ve had the ancient art as a starting point, and all the artists who showed great creativity in addition to the quality and consistency in the work.

The name Valeria Gramiccia is indissolubly tied to two great artists: Afro and Consagra. Do you consider it more a burden or a blessing? Is there a lesson you have received from the two that you feel ‘necessary’ to your present art?

I have always said that having such important ‘fathers’ was my great fortune. However, reaching my own autonomy was a long process.

What did Afro say about your work?

He only saw something. Every now and then I worked on my own while I was in his studio. One day he gave me a pack with all my drawings because, he told me, ‘The other day someone wanted to buy one. Take them home, otherwise they might think they are mine.’ Then he added: ‘Now you have to start working on your own’. He would have even supported me, but unfortunately he died, he had a stroke. Some sketches I’ve made are very much Afro style. So, in order to change, I started to make very clear pictures, which is not in my nature. Then I customized the job, it became completely mine. On the influence of great artists, I say it is better to have a father like Afro than to be the children of no one.

At the end of the ’70s you participated in the ‘Fronte dell’Arte’ (Art Front) in Matera along with other artists. Can you briefly tell us what your action consisted of?

Being one of the founders of the ‘Fronte dell’arte’ was completely random. I was in Matera as an assistant to Consagra: I would be the secretary of the committee but, lacking a quorum to constitute it (some artists who had joined the project had not come to Matera), I was promoted painter and a founding partner in the field.

The Art Front proposed and aspired to the participation of artists in the upgrading and restoration of historic centers.

Until the 1980s you devoted mainly to other artists’ care, making them known to the great public through exhibitions and documentaries. Yet in all this you have rather had a certain timidity to show yourself.

I have collaborated in various ways with exhibitions, catalogs, videos, but it was certainly not my job to change the fate of the artists I worked for: I always accepted to collaborate with the ‘biggest’ and working behind the scenes allowed me to observe them, to absorb and process their teachings.

On the occasion of an exhibition in Spoleto, in 1996, the artist Achille Perilli said: ‘For Valeria Gramiccia the narrative in the abstract sense is another key component that retrieves the meaning of a fairy tale: a way of telling that is not made from images of reality, instead it present itself like a memory of Arabic calligraphy, from the Arabian Nights, from Persian miniature or children’s book…’. Very often the artist is really he / she who can best preserve the childhood dream over the years and to remind those who persist in thinking about growth as abandonment of creative childhood.

My works represent an abstract story, a fairy tale, where every sign is a letter that by joining other signs forms the phrase and then the story to which everyone would give their own meaning.

The absence of shape in your work, make the quality of painting prevail. What elements make up a painting of good quality? And is it perceived by those who observe the work? Or in contemporary art there is always the need to be guided in some way to get to the essence of the work?

My works are not gestural: the forms exist, they are not naturalistic, instead they are well-defined. I do not think that non-figurative art needs explanations. It lives for what the eyes transmit to the brain. You sense the quality of the painting in the same way you perceive it in any other object. The viewer who looks at the work should not ask for the meaning. This is a question that an artist is not interested in. In my opinion, reading a work of art takes place on two levels. The first level is ‘I like or I do not like, it tells me something or not’, otherwise I step forward. If you see a picture of Mondrian you cannot ask yourself what it means. You can ask yourself ‘how it occupies the space’, that is the only meaning it has. Even in the case of a figurative framework, attention is focused on quality, if the eye is trained to observe. And the eye is educated by seeing. The second level works like this: if you like it, you go and look at it again and find out its quality, the reason of its quality, so you can give it a different interpretation. In the reading of non-figurative art, the essential things are how space is occupied, how you read the gesture of the author, his/her sign. The artists of the group FORMA 1, who fought realism, Guttuso, and the others, had the motto: LINE, SHAPE, and COLOR. They started from these things. Carla Accardi, Perilli, Turcato, D’Orazio, Consagra, line, shape, color. This is just the beginning of the Manifesto of FORMA 1.

What is it that was not enough in the figurative?

The avant-gardes have completely broken up any scheme. And it was not just a matter of style, even of message, of intellectual content. Let’s say that no one could ever reach Raffaello’s standards and the like. And then people were interested in something else. When Monet begins to make the Ninfee, he invents the word Impressionism, with the picture ‘Impression du soleil levant’ [1872]. He begins to break up, he no longer has the line of the horizon and the rising sun. He has a problem of light, only of light. He creates all those cathedrals based on light. And here you return to the point of feeling. Because if he reproduces the light that changes the facade of the Rouen cathedral, in the morning, at noon, in the evening, he looks at the light as it breaks up the shape.

Your matter is mutant, it does not subtract, it adds, it stratifies different weights and materials, from which you wisely make out your final realization. What is the process that leads you to this result?

The result must give a sense of ambiguity, weight, and lightness, and I get this by working for veils, stratifications. Starting with the light and then adding. Adding is easier than taking away. Like salt on foods.

Many of your works, the ‘bilichi’, are defined as ‘pittosculture’ [paintging and scultpture at the same time]. What are they and how many kinds of languages can they combine?

In the ’90s I felt the need to see what was going on behind the canvas I painted, what happened to the shapes I composed, seeing it no longer just for one side [the frontal one]. So the ‘wooden bilichi’ were born. Mirella Bentivoglio called them ‘pittosculture’ in one of her reviews. They were the first steps towards sculpture.

How is the idea of the bilico born?

The ‘bilico’ is born from the curiosity of seeing what is behind the canvas. That is, I usually create a painting that has only one dimension, one facade, if I work on the canvas; there is neither the second nor the third dimension. I only see a facade. How do the overlaps I did work here? How do they look from behind? A bilico allows you to know it. It assumes another form. You can see if it works even behind the canvas. The characters come out, take the liberty of encroaching. But they must obey me. It’s not like the mobil pieces in which each piece moves individually. Because it must stay in the way I’ve visualized it, and then we’ll see what happens. The shapes also leave the frame. The frame is a limit and I’m a rebellious girl!

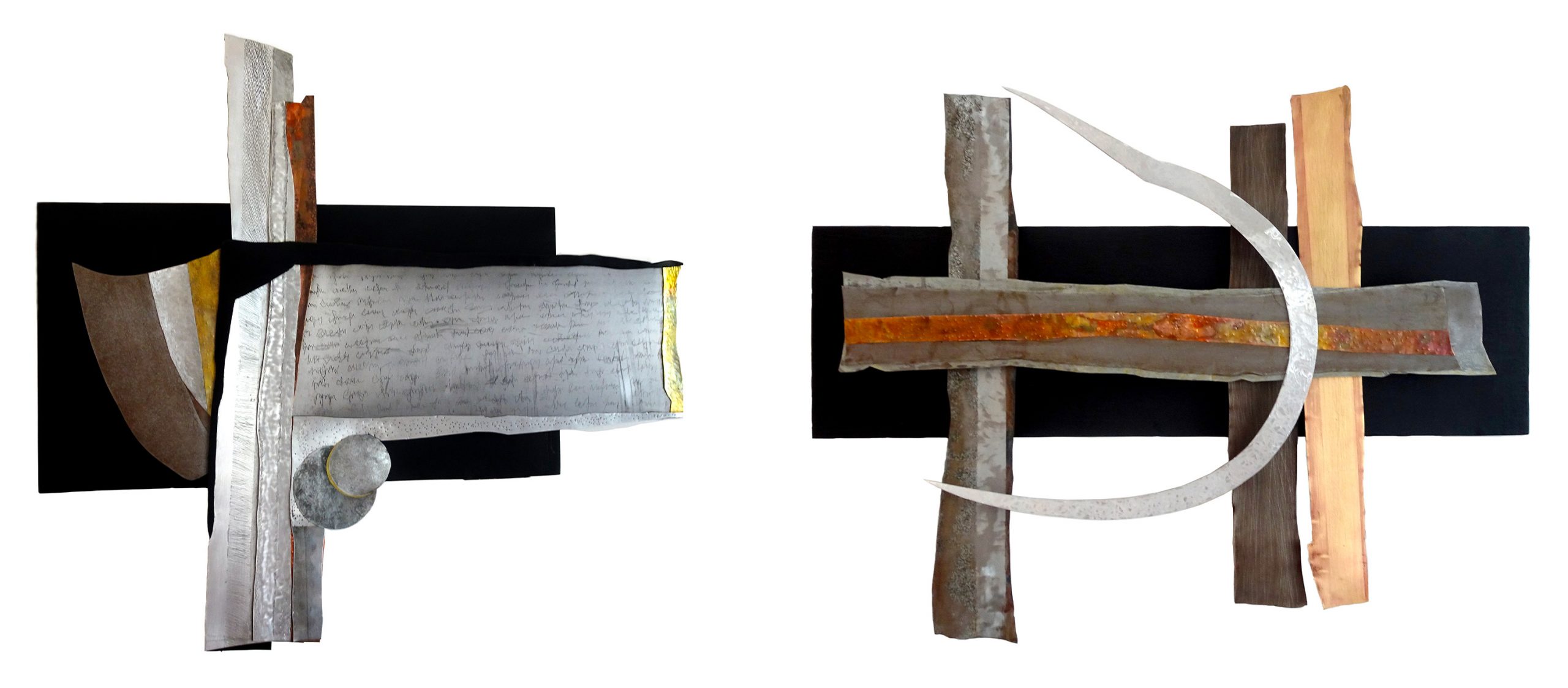

Talking about COMEL 2016 Award, you participated with the work titled ‘Grafie segrete’ [‘Secret Writings’], which was selected among hundreds of works from across Europe, and you received a major career award that has had international resonance because this is the spirit of the award. The tribute came directly from the jury led by the art critic Giorgio Agnisola. We can read in the judgment: “[…] artist who has lived from within and with great importance the artistic milieu of Italy of the last decades, both on a creative and historical-artistic level. She has collaborated in the scientific and organizational care of internationally important exhibitions and events, she was assistant to great contemporary masters. Today, she represents one of the most consistent and refined testimonies of the present Italian art. Her style, characterized by a light and secure sign, in particular in the graphic art, is between the abstract articulation and dreamlike dimension, and is at the same time at the juncture of the happiest tradition of abstract postwar expressionism and a cultured conceptual art, elaborated as a reflection of a rare and poetic expressive pronunciation.”

How was ‘Grafie segrete’ born and what are the materials that you have privileged for your works lately?

I was asked by the COMEL gallery to collaborate on the Afro exhibition they were organizing. Talking to the organizers, I learned about the contemporary art prize and I wanted to participate. I changed the material: I switched from canvas, paper, and wood to metal, but the work process remained basically the same. Overlays, fake transparencies, and to confuse everything, I used fake scriptures to leave the greatest interpretative freedom. I must conclude by saying that I got carried away by ‘Grafie segrete’, and since then I am working on both metal and paper, the material that I have always privileged.

You used one of your mysterious writings also in ‘Grafie segrete’. What function do they have?

It was a quest for materials. I work with glazes, stratifications, etc. The writings gave me the sense of the matter. I did not want to launch futuristic messages, so I started with fake scripts because they have nice letters. Let’s say that writing design is nice.

Such writing in the East is no longer a false writing, it is a writing that makes sense. Yours seems to me a work on the signifier.

It exists, it certainly exists, but as the characters are put in reverse order… Some time ago I made an exhibition in Viterbo, a very beautiful one… in a Sixteenth century hall. I put all the hanging ‘bilichi’. Some Japanese came to see the show and, poor things, they went mad to read the script. There is no hidden message. People wonder if there is Ungaretti here… [Italian poet]. But no, I say ‘read it with your imagination!’

Yes, it’s a work on the signifier. My work takes place as a story for me. There are various letters that make up the forms. I interpret them as letters that make up words.

How is your relationship with the materials? Which material you cannot do without?

The paper. My love for paper started many years ago when I went to Japan and in Kyoto my hosts brought me to a paper mill that was a magical place on the river where they made the paper.

See all of these? My first watercolors, I did several exhibitions with them. I’ve always worked on paper. You can do everything with it. These are the various sketches for the work presented at the Prize. I must say that the competition changed my watercolor, even my work on paper. It was very important. The paper is useful for putting on it the ideas that come to you. You cannot have the same immediacy on the metal. On paper you can see the work being evolved.

Is there any artist of this period that you follow, in whom you are interested?

Yes there is. At the moment, the artist I most admire is Roberto Almagno [1954], who is a wood sculptor. Originally from Aquino, he lives in Rome. He was assistant to [Giuseppe] Mazzullo, then he started to work on his own. He is very good. He’s having a lot of success abroad. In Italy there are currently no galleries.