VINCITORE PREMIO COMEL DEL PUBBLICO 2022

Interview with Claudio Marinone

by Ilaria Ferri

Claudio Marinone began drawing at the age of 12, learning the basics of drawing techniques. His great passion for calligraphy and illuminated letters exploded in the 2000s with the participation in numerous national and international courses. He became a listed calligrapher: for decades he has been working in calligraphy for private individuals, public bodies, publishing houses and for some of the major Italian fashion houses. His passion for figurative art leads him to emerge as a multifaceted artist, his works in fact range from drawing to painting, from advertising graphics to web design, up to look out in 2021 at the first experiments in sculpture.

“Nasce una musa” (a work winning the COMEL Audience Award, i.e., the most beloved by visitors to the Infinite Aluminium exhibition) is one of your most recent productions, perhaps the summa of your journey so far. How did it come about? How did you get the idea to enter it for the COMEL Award?

“Nasce una musa”, actually represents a path of growth, although its creation was itself almost accidental.

As for many of us, the pandemic year has led to necessarily having to fill time. Personal passion for artistic activities of various kinds ensured a good quality of life spent at home. Triggering cognitive processes prodromal to the study of materials that could be incorporated into some calligraphy-based artwork I had in mind. This is where the idea started and the subsequent processing of the work gave birth to a muse. It all came to life from the union of two different design phases.

In the continuous research and experimentation of new art forms, the first phase finds application and profile with the use of a common material normally used in far more humble functions: the steel bolt. The main challenge was to create works that would give an artistic form to conglomerate materials, through a painstaking, and nearly sartorial, operation of assembling thousands of individual pieces.

The effect of softness achieved, certainly not characteristic of a material that by rigidity and geometric uniformity is characterized by volume rather than ethereal form, transports the viewer to an atmosphere of sinuous and unusual harmoniousness.

Salvador Dali’s love of sculptural art led to the choice of subtracting parts of the figure rather than adding details, thus imagining feminine beauty in its most ancestral formation, which through the defragmentation of its parts is then regenerated in an act of love toward that inspirational image that for the artist is his wife: his muse.

In the next stage, attention is brought toward dynamism, speed and movement in the representation of the creation itself, which is interpreted through the other art dear to the artist, which is calligraphy.

It can be imagined that the use of calligraphic stroke and “fluttering,” transmutes the two-dimensional sign into the third dimension of space.

Through the use of aluminium ribbons, studying their curves and passages, the paths finally intertwine, and with their coils and sinuous forms the work wraps itself up, almost in a caress that gently touches the face of the muse as it regenerates into its human form.

My always competitive nature, the desire to put myself on the line, to place myself before the judgment of others with all that entails, creates in me a whirlwind of emotions that only such a manifestation can give.

The decision to participate in your contest came from this side of my personality. In February of last year, I had just participated in an art competition set up for the staff of the institution where I work and received a good response. It was the spring that encouraged me to search for a new audience, outside of possible personal knowledge. Through research on the web on a specialized site, I came across what for me will be a breaking point, an artistic turning point the announcement of the “Comel Award – Vanna Migliorin,” where aluminium is the protagonist and fil rouge of the entire event, characteristics that immediately lead me back to the work “Nasce una musa” thus presenting it to the competition.

Girasole, 2022 – Steel and aluminium

You are an established calligrapher. A very ancient art that has found a way to reinvent itself and continue to survive in this modern world in which even writing a note by hand has become a rarity. How did you get into calligraphy? What fascinated you the most?

From an early age, I loved looking at my father’s notes; he had grown up in a historical period where calligraphy, or rather the art of “beautiful writing” was still taught in school. I was amazed at how smoothly and, to me, wonderfully he could write. Whereas me, I had what I called “crow’s feet” or rather bad cursive handwriting as a child.

Partly for fun and partly to “make myself look good” to the girls, in high school I would write their names by inventing spellings, sometimes imaginative and almost illegible, effectively laying the groundwork for what I would later pick up for some work done for some brands and information campaigns. The real turning point happened with my wife, accomplice and inspiration for most of my best life choices.

It was 2002 and we decided to write our own wedding invitations and so began my journey into the calligraphic world. I bought pens, paper and ink, a nice book with the technical basics of some of the handwriting, effectively taking my first steps. The experience was wonderful, so much so that it led me to attend specific courses that were more and more advanced with the best Italian and international calligraphers. Courses not only aimed at handwriting but also at illuminated drawing, goldsmithing, page layout, and typographic techniques, up to the preparation of real hand-bound books.

Unfortunately, calligraphic works are essentially on commission and by their very nature unique. The artist is left with little tangible, save for a few sketches and proofs of ink-to-paper response. But the mental imprint and gesture acquired for each individual work remain a recognizable signature in many of my pictorial and sculptural works. An imprint that even in the case of the sculpture “Nasce una musa” was developed during the making, through reasoning and study of the transposition of the calligraphic gesture from the two-dimensional to the three-dimensional.

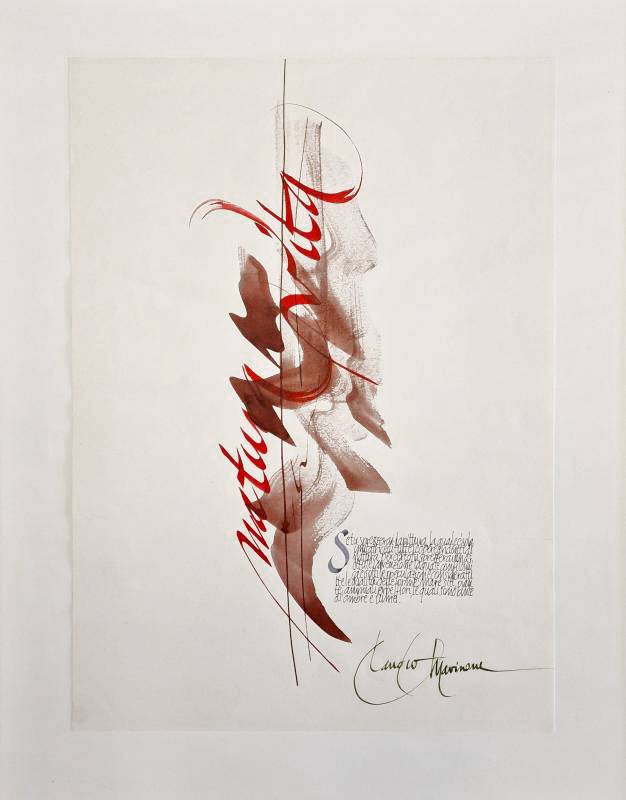

Natura e vita, 2022 – Tempera on paper

Speaking of “Nasce una musa” you state that the calligraphic “flutter” transmigrates into the third dimension by becoming sculpture. Looking at your path, is sculpture really the material and natural landing place of your experience as a calligrapher?

As I said, in the work “Nasce una musa” the portion of the calligraphic swirls is brought back into the use of aluminium bands, which are transformed into the “dynamic” part of the work and at the same time form its supporting structure. The portion that arises from the fluttering is transmuted into that which cartoonishly, leads back to movement, transformation and specifically the formation of the muse’s face.

So yes, the sinuosities reported in the third dimension, derive from the study of calligraphy where the curves of the swirls are never random, but are designed to harmonize the text understood as graphic composition. Most observers do not know that making a calligraphic swirl requires not only the study of passages but hours and hours of exercises useful to the hand and eye in order to train our brain responsible for perception.

Over the years you have devoted yourself passionately to illuminated letters, and work on mechanical technical drawing. Your attention to detail is striking, your propensity to narrow the field and to want to place a magnifying glass on a detail. This is well represented in various works (both paintings and in “Nasce una musa” itself) when you focus on faces and to be precise on a part of them. On what do you actually want to place the attention, yours and the viewer?

As you have rightly perceived, in my works the detail is important, certainly not as for a hyperrealist, where perfection leads the viewer back to an almost photographic image. Personally, I seek that visual perception that leads me to experience sensory emotions created by sight inducing the viewer to seek an individual point of interpretation, as if paradigmatic of Rorschach spots. So, I say yes, the detail is important to me when it evokes personal emotions in the viewer and that is what I try to propose.

Il mondo dell’Invisibile, 2022 – honorable mention of the international competition “Luxembourg art” 2022

You state that, as an artist, what moves you is the quest to externalize the inner and to communicate “your beauty,” beyond fashions and more impactful painting. In what does your beauty consist? What do you feel you urgently want to communicate?

After all, this question is the summation of an inner product. Beauty is personal, is its own, a banal but not indifferent phrase in art, indeed.

Unlike the communicative message that is uniquely understood, the perception of beauty, in any work, is the result of the proposer’s feeling as opposed to the sensations of the viewer, of the appreciator, devoid of the “personal epidermal” attraction. In one’s interpretation, the observer creates his own beauty as personal, subjective data. My goal is conducted in the search of this subjectivity, for those common points that stimulate its sensations, its visual fulfilment.

Clearly, I, too, cannot escape from identifying themes that can be traced back to broad, easy-to-read messages, such as nature’s cry for help, the power of architectural beauty, and the harshness of loneliness, which I nevertheless consider the facade of a deeper quest.

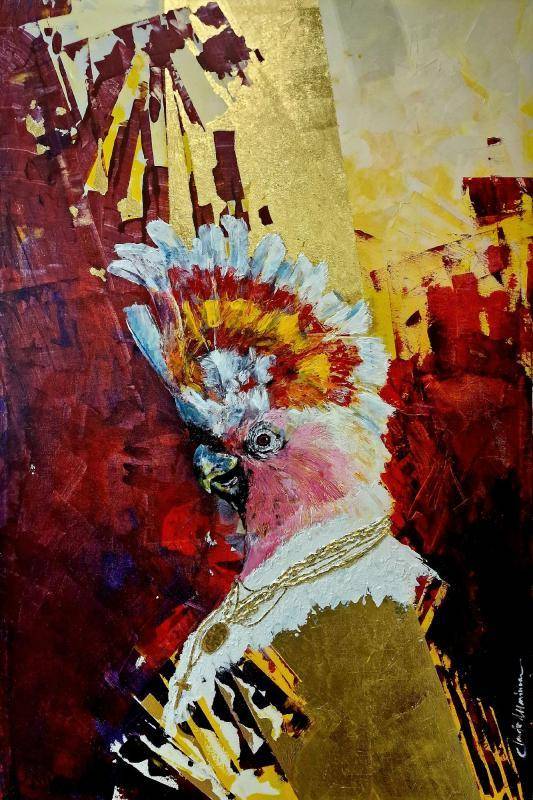

Mitchel, 2023 – acrylic paint on canvas

Drawing, painting, calligraphy, and lately sculpture-you are an all-around artist who spaces three different techniques. Which of these do you feel most comfortable with? How does the desire to try your hand at new languages come about?

I start by answering the second question, which is about imagination. Actually, every technique for me is experimentation, being in some fields self-taught, even in those classic techniques, the most historicized ones, there is always something of my own, a modification. This stimulates my imagination and the desire to find new ways.

The example: many people asked me about the process I used for the work submitted to the competition, when I explained that actually the steel part was not welded but glued, everyone looked at me like a fool, wondering how a two-component glue could hold such a structure. Making people understand that it took me almost four months to find the right square that would allow me a good mechanical seal and at the same time grant, to those who look at it the feeling of something that was being formed and created from the inside. I kept trying different materials, only to find that one of them melting left a hard, tough residue. But this little secret I will keep to myself….

Now to tell you which technique I feel most comfortable in, excluding the calligraphic ones that now live on two decades of experience, is perhaps metalworking. The art that teases me today and in which even not being a craftsman of the material gives me that facility and factual naturalness that I have not had in other artistic forms.

I am sure of one thing, however, I simply “HAVE FUN.” As long as there is this spirit, other forms, techniques, and experimentations even made with several hands, in collaboration with other artists or craftsmen who want to share the fun with me, are welcome.