COMEL AWARD 2023

Interview with Pietro Finelli

by Ilaria Ferri

He studied architecture at the Federico II University in Naples. An artist, curator, and theorist, he lives and works in Milan. He has exhibited his work in galleries, museums, and international institutions, including MC Gallery in New York, Il Ponte Contemporanea in Rome, Pack Gallery in Milan, Castel Nuovo Museum in Naples, Fundation F.J. Klemm in Buenos Aires, Galerie Jacques Cerami in Charleroi, Pietro Monopoli Gallery in Milan, IULM University of Communication and Languages in Milan, Chateau Gilson in La Louvière, Belgium, Pio Monte della Misericordia in Naples, Muzeul Național de Artă al Moldovei in Chișinău, and KCCC (Klaipéda Culture Communication Center) in Lithuania.

Your participation in the COMEL Award earned you a Lifetime Achievement Award, recognizing your ongoing commitment to visual research between Art and Cinema. How did they come into your life when you thought they should be your field of inquiry?

You asked me about art and cinema together. I was three years old when my father took me to a movie they programmed in the morning at the cinema. It was different than watching it on TV, and the big screen was bewitching in that darkness; indeed, the darkness and the light of the screen with the moving images were intertwined and defined together. What fascinated me, years later would consciously enter my field of inquiry. This paralleled with the interest and development of art, which was beginning to articulate itself in its various ramifications and complexities.

Some, oversimplifying a lot, define cinema as “art in motion.” Still, you use these two languages, Art and Cinema, for ongoing and in-depth research on human perception and its complexity. The image, for you, is a way to deconstruct the narrative and get to the core of understanding and learning. Your artistic journey becomes a philosophical quest through the visual element; could you tell us about that?

For historiographical reasons, there is always a tendency to simplify what, at first glance, seems to be the connoting element of that particular media. In this case, the definition of cinema as art in motion is reductive and schematic, but, at the same time, it is iconic; it defines what somehow distinguishes it from other media. Now, I found it interesting, as I have been trying to show for some years now, this ‘likeness’ between Baroque painting in the Flemish and Spanish context, particularly in the work of Velazquez and Pieter De Hooch on the theme of doubles and visual unwrapping that undermines Renaissance perspective representation, and some of the masters of modern cinema, particularly in Hitchcock, Fritz Lang, Welles, Edgar G. Ulmer, to name just a few.

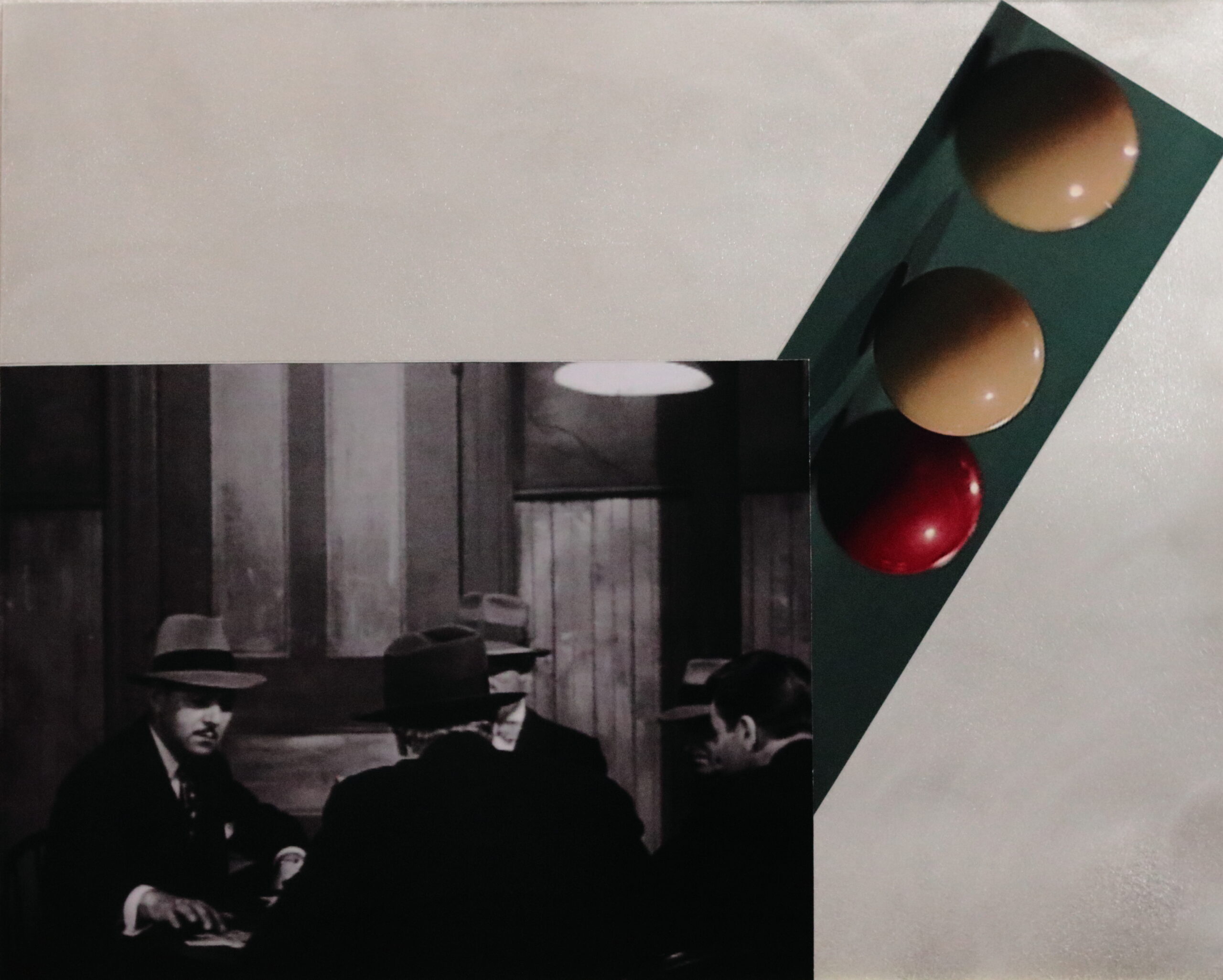

Noir aluminium 5, 2023

You participated in the tenth edition of the COMEL Award with the work Film, of which you state, “In this work, aluminium marks a rhythm, but itself becomes a cinematic frame of the abstract, reverberating tensions, like a film with a desiring progression, with multiple references, a sort of noir machine lowered into the psyche and physicality of the world. Almost as if the aluminium made the mist of film noir solid and three-dimensional, those glimpses of light in the darkness. What does it mean to you to try your hand at this metal?

One of the things that has fascinated me about this material is the extreme flexibility of being both an object and a work of art, somewhat like the canvas that is an object in itself and a work of art once used by an artist. All materials, as we have been taught from the historical avant-gardes onward, have this ability to be objects and displays of concepts. I wouldn’t say I like those formal exercises that depower a material, in this case aluminium, to make it a mere shell of exhibited superficialities. Think instead of artists like Beuys, who used aluminium by ‘bending’ it within a highly complex visual discussion, or an artist like Walter De Maria, in whom aluminium is interpenetrated – here really – with that spirituality understood as purity of thought. In my use of aluminium I have these components present, I think it ‘lives’ out of this duality of object/work.

Painting, drawing, photography, installations, your field of action is articulated according to various languages and techniques, are they functional to the conceptual discourse you pursue and therefore carefully chosen from time to time or are they part of a process of technical-artistic experimentation?

I am especially interested in painting and drawing. I like to check and trespass on other languages that interact with painting and drawing. I am interested in an idea of cinema that relates to an idea of painting or drawing and then about the meaning and significance of these languages in the contemporary world. I am not interested in experimentation for its own sake.

Noir aluminium 5, 2023

Much of your artistic path is related to Noir, of which you totally shake off the narrative part to concentrate on style, which takes on themes, ideas, and obsessions. You preserve the atmospheres of this genre but decontextualize individual frames to grasp their deeper meaning. How did the idea of this kind of process come about? What attracted you to this film genre?

I want to quote one of Paul Schrader’s Notes on Cinema Noir (1971), which, in his definition of film noir is a “moral vision of life based on style,” “capable of resolving conflicts in visual rather than thematic terms.” implies an art that in its visual power absorbs and incorporates the themes of representation and conflict-which I subscribe to-but is also a way out of certain problematic, so prevalent and present in so much discursive, “committed,” tautologically self-referential art, a type of art that wants to fulfill a “function”.

Saskia Readel says about your exhibition Noir Time, “The compulsion to understand, to learn and to comprehend only exists if there’s darkness before. …. Pietro invites us to immerse our mind and body into Noir Time and develop our own personal meaning of it: of life, of logic or just of the meaning of film noir.” Light and darkness are fundamental elements of your painting, not so much in the classical sense of chiaroscuro but as a dualism that allows you to shape things and, at that moment, understand them. How, in your opinion, do light and darkness allow the understanding of things?

I have never understood light and darkness as a duality or even with ethical-moral connotations. Darkness is light, light is interpenetrated in and by darkness. This tension generates new ways of seeing. A painting of mine is a geological layering of mental and physical states, relative to the world and to my being an artist and to that lump constituted by the material out of which painting is constructed. Now for it not to be just an exercise in style, it is necessary for this layering to have its own ‘poetics’. Poetics, for me, is understood in the Aristotelian sense of the term, thus as knowledge. This device, which we call art, is also a center of relationship, living not only for itself, but together and with others.

Noir aluminium 7

Adrian Dannat states, “For over the last two decades, Finelli has surely developed his own multi-form, many-layered, hyper-sophisticated strategy, by which to navigate/ negotiate our current ocean of image-culture, buck it.” In recent years, image culture has been further enriched with the rise of streaming platforms and the proliferation of movies and TV series that are not enjoyed in movie theaters. In your opinion, this bombardment of images to which we are subjected every day can be detrimental to Man and Art, or is it a stimulus to look for in the multitude of what really has value and meaning?

That’s a good question! It is not the bombardment of images that harms, but their use. With new technologies, we are doing things that were unthinkable a few decades ago; even art is trying to expand using these same technologies. The exciting thing is that in the presence of these technologies, painting, and drawing do work that on the surface seems to be marked by tradition, as it should be, but in the most alert painters, a conversion and repositioning of painting takes place, capable of illuminating and relating to our world, more and better than many technological media. Which, in the frenzy imposed by the capitalist laws of the commodity with the compulsion to the ever-new, make those things produced that seemed avant-garde grow old and retrograde. These juxtapositions are of the old guard, put into crisis already with the advent of photography and then by the cinema, but which instead in the most alert artists and filmmakers, to return to our discourses, become flywheels for novel adventures and situations.