THE 2017 COMEL AWARD FINALISTS

Rosaria Iazzetta

Mugnano di Napoli (NA), ITALY

www.rosariaiazzetta.com

www.rosariaiazzetta.com

THE 2017 COMEL AWARD FINALISTS

Rosaria Iazzetta

Mugnano di Napoli (NA), ITALY

www.rosariaiazzetta.com

www.rosariaiazzetta.com

BIOGRAPHICAL NOTES

She lives and works in Mugnano di Napoli (in the province of Naples). Professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Naples, she has an international background, while remaining attached to her own native land, both from an artistic point of view and for her social commitment. She is an expert in metalworking, in love with photography and proactive slogans as symbol of cultural commitment. In fact, she is a narrator who uses metal to process new creatures, born from carcasses otherwise destined for landfill. Her contributions and international exhibitions between East and West are copious. Sculptor-craftsman, she prefers the welding process and considers the creation of a sculpture an ethical and emotional ritual.

ARTWORK IN CONTEST

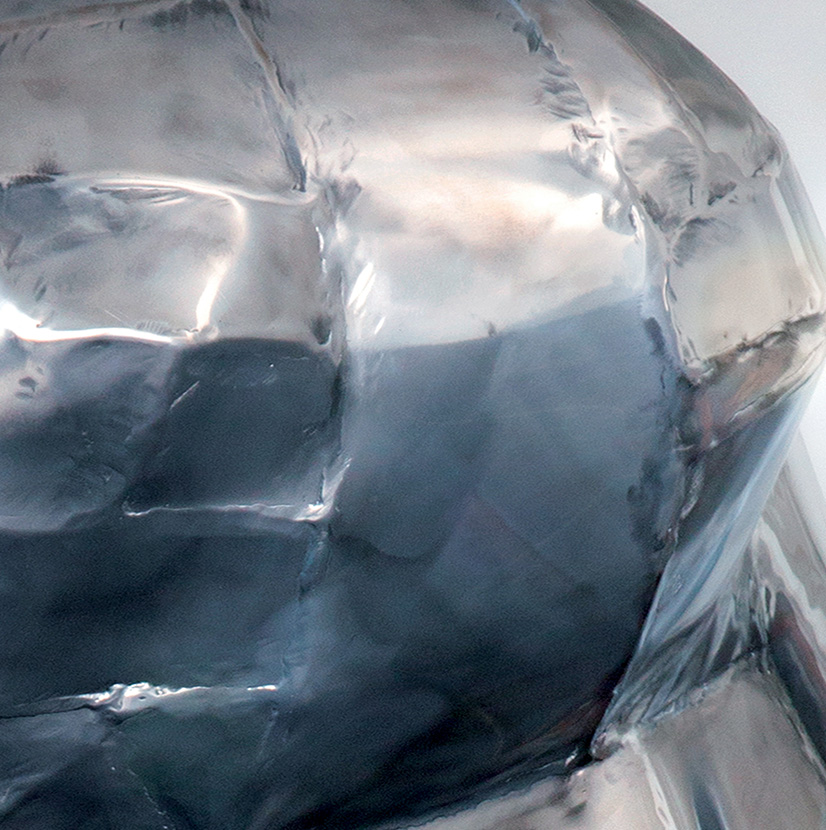

SENZA TITOLO, 2016

SCULPTURE - Tig welded and mirror semi-polished aluminum

cm 89 x 145 x 120

The work of Rosaria Iazzetta (Untitled, 2016) might be partly metaphorical. It elaborates a vaguely anthropomorphic form, referring to an adulterated, polluted and lost nature. However, the object built by the artist, beyond metaphor and its formal equivocation, attests to an evocative visual organicity. Perhaps to indicate that, despite everything, in the art, unity is recovered, beyond the visible, even in the monsters that invade the soul.

AWARDS

WINNER OF THE COMEL AWARD 2017

with the following motivation:

“The work imposes itself for its strongly allusive design of anthropomorphic nature and for its specific and evocative metal work, molded and welded with great expertise. The final result is an original and humanized shape outlined in a dramatic and futuristic way.“

Interview by Rosa Manauzzi

Those pieces are like comets that agglomerate, like particles that add up, or cells that live their own life and then together create a single body or a single organism.

Rosaria Iazzetta, you were born in Mugnano di Napoli. When did you approach Art for the first time and what is the path that has led you to become an artist and teacher of sculpture, at the Academy of Fine Arts?

Well, I cannot recall the exact moment. It was more of an instinctive need for me, like loving or eating. I was just under ten years old, and I felt the need to assemble and disassemble things. I used to transform any object that was given to me, even if it lost its initial value. I haven’t visited many museums as a young girl, and that made me suffer a bit later on, but I was lucky enough to live outdoors, so at the age of fifteen I was sure I would become a peasant. I have always loved physical fatigue. I thought I would become a runner at times, because I loved the effort to overcome time while running. I soon realized that I could not follow the advice given to me by the teachers at school. My notebooks clearly showed a creative need to invade the writing with shapes and colours. The College and then the Academy came. I could not choose different studies, perhaps because that was the only barrier of containment to a fervour that I felt inside, like a mixture of ecstasy derived from curiosity of knowledge and manual experimentation. I do not think I ever decided to be an artist in fact. Over the years I have collected an indefinite amount of material, which I experimented and assembled, until it was integrated and worked on, in order to make it aesthetically functional. Two events were instead meaningful for me in awakening my awareness of sculpture as an expressive means, and of certain forms as a language: a ship in a repair basin, out of the water, at the Port of Genoa seen when I was 17, and Bilbao Guggenheim in Bilbao, by Frank O. Ghery, visited when I was 21. I didn’t sleep for weeks afterwards. As if those scenes belonged to me, but I had never seen them before. I chose to become a professor when I realised that I was able to give, at least in part, what I would have expected to receive when I was a student at the Academy. I’m not sure I’ve succeeded, but I always keep this in my mind. We need to give priority to young people, to their expressions. They are the levers of revolutions and resolutions in these cathartic moments.

The installation through banner and photography has characterized your civil commitment for several years, and continues to be reflected in your work, with projects dedicated to suburbs and schools. Among the phrases used in the banners, always with a strong emotional impact, you have chosen one by Paolo Borsellino: “At the end of the month, when I receive my salary, I always ask myself if I have earned it!”, and other messages which invite us to recognize feelings and values as part of a necessary empathetic correspondence with the territory. At times, these are huge, yellow, and visible from great distances. Have you ever had trouble installing them on public buildings? What was the attitude of those who observed the preparation of the installation? Have you ever been afraid?

Of course I have. I was scared many times, and I have even received threats for some installations. The fact is that I always let myself be guided by a motto: “If you always look the other way, sooner or later you will pay!” If I had surrendered, I always said to myself, I would have stopped believing in a different future; all the indignations I had would have made no sense, and would have become frustrations. Many have preferred to leave, or become ill, giving in to aggression or abuse. I wasn’t then, and obviously I am not today, willing to give in. I think a lot of people still need to become aware of certain issues, especially those clearly irritating and violent in Campania, and rebelling against these issues is still a rare act, which unfortunately doesn’t find many followers. In my own little way, I do not think that I should renounce the idea of legality and social justice, but I should instead continue to believe in it, always keeping in mind the feeling of community of these decisions.

Ritorno del bene, 2011 – Light-box, alluminio

The metallic object that you create with your hands and your tools, acquires fullness and at the same time still maintains spaces to fill, as though you had a fear of hiding, concealing. The works often preserve a respectful emptiness to be filled with the surrounding reality, of those who experience it or perceive it. Where do the shapes of your sculptures come from?

Many of these shapes have been defined over the years, with constant research and study. I have rarely worked on shapes without studying them in advance. The gestation for a sculpture is perhaps the most important part. Understanding size, material and static quality goes hand in hand with the value that they will carry. I have always wanted these shapes to describe the distress, or the dynamics we know well but that are not visible to the naked eye. The goal was to give a shape, trying not to be ostentatious, but sharp; to represent a precarious state at times, with stability mostly on three feet; in just one case on four feet. I have removed the basic concept, completely, because as anthropomorphic as they are, they are always pointing upward, to a dream of lightness; they resist as much as possible, they illustrate, using curves or straight lines of steel or aluminium, a political and social indigestion. The voids, sometimes visible and sometimes not, are the constant in these sculptures. It is there that the spectator’s eyes always settle. That shape change, that definition which is not perfect or even linear, which pushes to fill the void, with the remaining story of the discomfort that the viewer carries inside. I want them to be empathic sculptures, before being attractive, for brightness and material, in order to create a closeness with those who observe them; in the end the sculptures tell the states of anger that we tend to dampen, and that involuntarily, depending on the states of evolution of the soul of the observer, tend to soothe or stir up outrage.

The work Senza titolo (2016) won the COMEL Prize of the jury of the sixth edition with the following motivation: ‘The work imposes itself for its strongly allusive design of anthropomorphic nature and for its specific and evocative metal work, moulded and welded with great expertise. The final result is an original and humanized shape outlined in a dramatic and futuristic way.’ It is a scary sculpture, bent to the sinuosity of the workmanship, thus responding to the title of the exhibition connected to the Award. In the presentation of the work you mention that it is ‘an integral part of an extremely important and urgent narrative work’, dedicated to the environment that surrounds us and to ecological ethics. Do you want to talk to us about this narrative project?

Sure. The work in question is part of a larger project, which involves two other sculptures taking part in an installation. The work, created on the occasion of the ‘sandwich’ exhibition, inaugurated at the E23 gallery in Naples last year, was completely structured on the havoc perpetrated in the agricultural and peripheral areas of Campania. In fact, the title of the exhibition refers to the system of burial in layers of toxic waste, adopted by the “underworld” and described by Schiavone, one of the few bosses of the repented Camorra. The work consists of three aluminium bodies which, by position and shape, circumscribe a laurel tree now lifeless. In the air that cut through the shapes, they try to stem the drama, but they are nevertheless vibrating with such a state of corruption, that they give in to abuse; from defenders they become usurpers, from controllers they turn into material executors. The bodies, missing the upper trunk, the head and the heart, placed on three legs, have in common a convergence towards the trunk of a leg. The legs, albeit at different heights, align themselves with the shape, and they perform the landfill and death procedures without intrusion, with intransigent abuse.

Cavallo di ritorno, 2007

Your stay in Japan, from 2000, thanks to the first scholarship you won, which was offered by the Campania Region for the best academic thesis project, and your subsequent study experiences, at the Department of Sculpture, as well as the experience at the Shinkokurizu Opera City and the Italian Institute of Culture in Tokyo, as a teacher of Italian Language, gave you the opportunity to acquire the language and culture of a very distant country. Beyond these data, not at all obvious, which intrigue us, what was more important for your enrichment: to emphasize the difference between Italy and Japan or to stress their similarity? On what did you focus your research on?

Let’s say that Japan was a dazzling experience for me. A system of laws and a peculiar way of communicating, applied to a whole Neapolitan existence, have created contrasts in my soul, but also extraordinary surprises. Studying at the Department of Sculpture of the Tokyo University of Arts, above all defined the iron matter in my sculpture. The university structure, divided into sectors, has specialized the relationship with this subject, and made it significant within my career. It is clear that the social and cultural lives of Japanese and Italian people are completely different, back then as well as today. However, I have always noticed that most of the social events that took place in the East, also happened in Italy a few years later. In the diversity, to which we are more or less attracted, we find inner similarities, which certainly allow us to evolve. I would prefer to talk about acquisition of new visions, rather than evolution, as it is too early to tell. The eyes remained the same, to my regret, but for example recognizing the ethical sense between some quirks, in Japan, and not having to desire other things, which I cannot afford, has driven the concept of lack of ethics in Italy and specifically in Campania. That diversity was necessary to fully understand the things I was giving up in the first place, and to which we are all giving up. It is clear that perfect places do not exist. It is a bit like in the end of the 1988 ‘Tokyo Pop’ movie by Rubel Kuzui, where the protagonist, a foreign rock singer, arrives in Tokyo and feels confused, despite living an extraordinary experience with her new Japanese singer partner: only by going to places where you have never been before, you understand who you really are! Obviously, if you feel like you belong to some places, this is another matter. However, it is a good reason to build a comparison and analysis on the work that you carry out, in a constant manner.

In your creations, welds are clearly visible. They almost look like scars to boast about. Your sculptures disturb, they seem creatures of other planets ready to move their own lives. The impact is immediate and ‘provocative’. Embellished and polished, they remind of the ancient Japanese technique of Kintsugi (“repair with gold”). In general, ceramics undergo this process of rewelding and are then embellished with a thread of gold, silver or copper powder in the grain. You often tend to go back to your work and embellish it too. And above all, getting back to the subject of Kintsugi, the imperfection of anything offers strength and charm, compared to an alleged perfection. In short, every scar is the crack in which light passes and transforms, strengthens, firmly. In the scars of Burri there is suffering and beauty. In the scars of your sculptures there is dynamism and resistance.

Let’s say that leaving my mark on the pieces that are joined together is a priority for me. Those pieces are like comets that agglomerate, like particles that add up, or cells that live their own life and then together create a single body or a single organism. I believe that when we look at our navel, we can sense where we were connected and where we took nourishment, but we cannot live that experience, we have been there, but we were too small to understand that miracle. That mark remains, and fashion has even given to it an important meaning, it is no longer a detail, but part of a whole. I would like my works to be seen in these terms: they are signs of creation, where – despite the fact that nobody was with me while I was working them, while the heat of the welding put them together – the whole gestation is clearly visible. In these signs, I do not think we should read the discomfort, because that is what the shapes are for; they rather indicate a sense of belonging, of feeling part of something.

Rosaria Iazzetta nel suo studio

We have the righteous and we have the Camorristi, we have the engaged citizens (in social, in culture, in politics) and we have the living-dead, as you called it. The first will be remembered, the second ones will disappear. Or that’s how we would like it to be. However, it seems that oblivion for those who harm society is not so obvious and immediate and, on the other hand, it is rather certain that many cultural and artistic environments still live in inaccessible ivory towers. What would you like to say to those who create art, to those who promote it, to those who want to spread culture? Which strategies should they activate to achieve cultural goals?

We need to make a distinction between cultural goals disguised as political interests and manoeuvres, and cultural goals where the target was really to support culture. The line between these two modes is subtle, and one often overflows into the other. I have known realities, rooted in the territory, that have built a cultural network, without any other resources but human ones, with the result of various social miracles. In other occasions, instead, there has been an appalling waste of money for events that had absolutely nothing cultural about them. It is necessary, in my opinion, to always make local communities aware. The radical nature of a project depends on the integration and involvement of the inhabitants. Keep in mind that even a work commissioned to Richard Serra, has been located elsewhere, when the people decided they didn’t want an iron wall as a tenant in the square! We must then deal with administrative representatives and/or promoters from a high ethical profile. Successful structures don’t always have ethical values, and compromising is always unproductive in the long term, if you think that the advantage is just an extra newspaper article and that, if all goes well, after two years the same newspaper will be used to pack the glasses during a move, or it will be recycled, or even burnt to start the fire in a fireplace! I invite all artists, anyway, to not give up. It is very easy to indulge in something else, especially when you are surrounded by family members and loved ones who have stifled their own creativity. On the contrary, there is nothing worse than artists who, standardized by the system, build artefacts that reflect the will of the economic system rather than their souls’. It is necessary, in my opinion, to remain within oneself and connected to what is produced because that is our projection, a part of us, that we would not want anyone to mistreat or denigrate, but rather to act as support for others on our path towards the truth.

Anticipating Bauman’s Liquid Modernity, Pirandello wrote at the end of 1800: ‘When the old norms have collapsed and new ones have not arisen yet or new ones have not been established, it is natural that the concept of the relativity of everything has become so large that our critical judgement has almost been completely impaired, leaving the way open to any assumption. Human intellect has acquired an incredible mobility. Nobody seems to have a firm and unshakeable point of view… I believe that our life has never been more ethically and aesthetically disrupted than now. It is untied, without any principle of doctrine and faith….’ (“La nazione letteraria” of Florence, “Arte e coscienza d’oggi”, September 1893). Your art originates or has anyway a strong connection with the social function. And, free from ideology, it feeds on very firm points: awakening of conscience, legality, civil participation. How do you fit in today’s liquid society that seems disinterested in such values that are also aesthetic?

I cannot ask myself how I fit in, even if you are asking me that now, because I tend to do it by necessity, rather than by reasoning. My aesthetic values, for example, are not in the art system, but that doesn’t mean that I stop creating and narrating social aspects; on the contrary, I work even more in order to find alternative tools and systems, external or foreign, in order to continue to spread my message. The lack of certain values is for me a fertile ground to work on, that is, I do not believe that I have the power to bring certain values back, because I do not have the necessary requirements, but my need to create tries to propose a social use, a sharing that can invite to ponder over matters of extreme importance. Obviously my products are not a primary need, but nowadays in a society that has forgotten that breathing, rather that personal achievement or material goods or happiness, is the most important thing, when I create my sculptures I try to think about my breath, because while working I feel alive, and I get oxygen. I give food for thought to those who want to know stories of truth.

You are also the author of a photographic book, a way to create art while looking for a more direct relationship with the user. Bad tolerance: Happiness wins when hope and conscience stop being fugitives (2011). You said that the habit of beauty helps to recognize monsters when they appear. Hence the function of Art as an instrument of beauty and knowledge, but also of an unveiling, just like in the book, in which you portray the harsh evidence of people who come into contact with the underworld (as a victim and/or as a witness).

I was returning from Japan, and I felt the need to gather the evidence of what we all know but do not say. To talk about the truth! For me photography has also been an important tool for revealing the truth, and so when putting photos and texts together I thought it would be appropriate to give a more intimate and direct narrative, to what the Camorra daily does, and to which we are all forced to give up. The only claim that the text proposes is to give hope. In fact, the text ends with blank pages, where you find the stories of people that have fought against the Camorra without giving up, because they believed in the fight, the best social tool for the collective well-being of the soul.